Aerodromes 139 vs CAP 168 – A Tale of Two Obstacle Limitation Surfaces

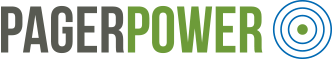

Development in the vicinity of an airport is restricted in part using invisible surfaces called Obstacle Limitation Surfaces (OLS) which slope upwards and outwards from it. The surfaces were first designed in the 1950s and they restrict the height of new development, in order to safeguard air traffic movements including take off, landing and circling. There is currently a task force in operation seeking to introduce a fundamental change to the way these surfaces are formulated, accounting for changes in the performance of aircraft and the layout of towns and cities that have ensued over the past seven decades [1]. In this article, however, we will explore the plethora of different guidance on the subject applicable within the UK.

OLS – Introducing the Various Rulesets

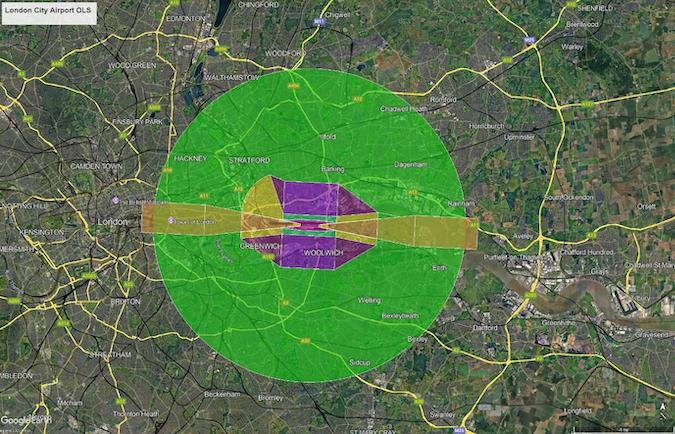

Aerodromes UK Regulation (EU) No 139/2014 (Aerodromes 139) [2] and CAP 168 [3] are two regulatory documents that outline rules on Obstacle Limitation requirements in the UK. It is worth noting that all OLS are a derivation of the guidance set out by the International Civil Aviation Authority (ICAO) in ICAO Annex 14. Some derivations are more faithful than others. Some countries use the ICAO rules outright whereas some, particularly larger countries such as the UK with better resourced aviation authorities, see fit to adjust the rules to their needs. Most of these changes are quite minor and consist of changing the dimensions of already established surfaces by a couple of metres, but there are some prominent examples of OLS being formed where new surfaces are introduced or existing surfaces changed completely. These include the bespoke surfaces at London City Airport in the UK [5], and the American surfaces defined in FAA part 77, which translate the measurements into imperial and introduce a new primary surface [6].

Besides the exception related to London City Airport, the UK has four main documents which pertain to the rules surrounding OLS. Civil aerodromes are covered by CAP 168, CAP 738 and Aerodromes 139, and military aerodromes are covered by Regulatory Article 3512. This article focuses on CAP 168 and Aerodromes 139. These are both documents which outline the design and safeguarding rules for civil airports in the UK, including their obstacle limitation requirements. Their slight difference is that Aerodromes 139 specifically refers to the certification of aerodromes, and CAP 168 specifically refers to the licensing of aerodromes.

Figure 1: London City Airport has unique Obstacle Limitation Surfaces.

Licensing vs Certification

The process of certification is set up by ICAO as a way of enforcing the regulations it sets out for various aspects of aerodrome design and safeguarding. ICAO makes the recommendation in its Annex 14 that “States should certify aerodromes open to public use in accordance with these specifications [contained in ICAO Annex 14] as well as other relevant ICAO specifications through an appropriate regulatory framework.”[4] In the UK “the term ‘licensing’ is used rather than ‘certification’”[3] and the standards required to be a licensed aerodrome are set out CAP 168. This licensing specification is effectively enforced by a requirement in Air Navigation Order Article 208 which requires that flights used for public transport and teaching take place only at licensed aerodromes. [3]

There is a slight complication with all of this that has been caused by Brexit. The UK was, prior to Brexit, a European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) member state. This meant that the UK followed EASA rules including those rules about the certification of aerodromes. These EASA rules are set out in another document called Certification Specifications and Guidance Material for Aerodrome Design [7] and these rules particularly are very close to those set out in ICAO Annex 14. The status of the UK as a former member of the EU means that many of the larger aerodromes in the UK are currently certificated aerodromes as opposed to licensed aerodromes, and these aerodromes follow the guidance as set out in Aerodromes 139.

Aerodromes 139 vs CAP 168 – Applicability

What are these differences which exist between Aerodromes 139 and CAP 168? Aerodromes 139 effectively inherited the EU rules contained within [7] and to this day, the dimensions of the OLS have not changed, which means that certificated aerodromes within the UK have the same OLS as all European aerodromes which are certificated by EASA. CAP 168 contains an adaptation of the rules specifically for UK airspace, and these rules are similar to but not the same as those contained in Aerodromes 139.

Aerodromes 139 and CAP 168 – Technical Similarities

Let us examine the similarities between the two rulesets first. The Take Off Climb Surface, which safeguards the path of aircraft taking off; and the Transitional Surface, which safeguards the area immediately adjacent to the runway strip; are identical across both sets of rules. The Approach Surface, which safeguards aircraft on final approach to a runway threshold, would also be identical for the overwhelming majority of runway thresholds. The sole exception to this would be for an instrument runway less than 1200 metres in length (code 1 or 2) with a precision instrument approach. In this latter case the approach surface extends further out for a certificated aerodrome than it does for a licensed one.

Aerodromes 139 and CAP 168 – Technical Differences

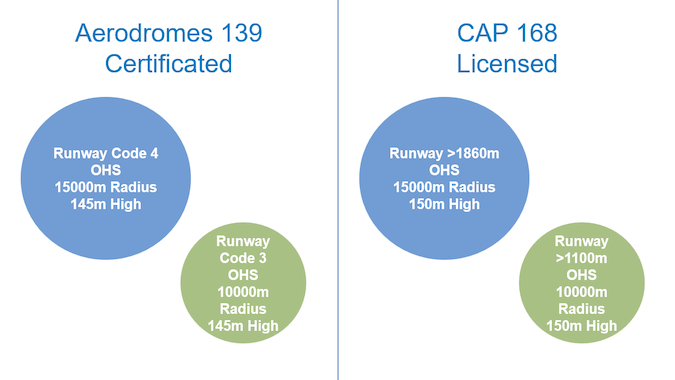

The true discrepancies arise when we look at the Inner Horizontal, Conical and Outer Horizontal Surfaces. To start with, the height of all Outer Horizontal Surfaces (OHS) is 150 metres above the lowest runway threshold in the case of CAP 168, but 145 metres above in the case of Aerodromes 139.

The radius of the outer horizontal surface also varies. Airports with a runway longer than 1860 metres have an outer horizontal surface of radius 15000 metres regardless of which rules they follow, but when the runways become shorter, things become more complicated. The rules in Aerodromes 139 are fairly straightforward: Code 4 runways have a 15000 metre OHS and Code 3 runways have a 10000 metre OHS. The Outer Horizontal radii for licensed aerodromes are instead based on runway length, which is not quite the same as runway code number. Here, runways longer than 1860 metres have a 15000 metre OHS, longer than 1100 metres a 10000 metre OHS and shorter runways no OHS at all.

Figure 2: Comparison of Outer Horizontal Surfaces present at Certificated and Licensed Aerodromes.

The Conical surface is quite similar across both sets of regulations in that it always has a 5% gradient, but the widths are different with the Conical surfaces for licensed aerodromes typically extending further than those for certificated aerodromes.

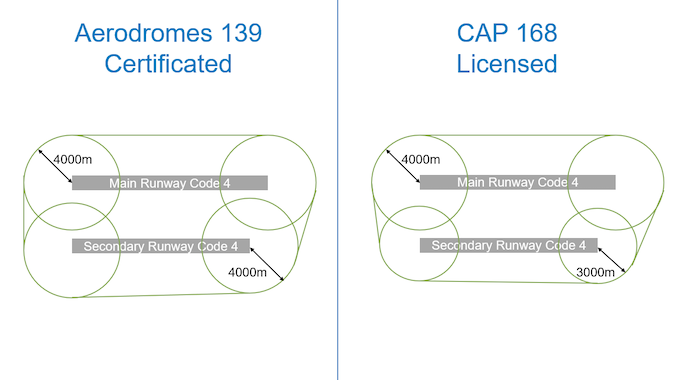

Inner Horizontal surfaces are always at a height of 45 metres above the threshold. Here, the main difference in the rules concerns what to do in the presence of a secondary runway. Aerodromes 139 treats all code 4 runways equally – if there are multiple code 4 runways at an aerodrome then the inner horizontal surface will consist of a locus of 4000m arcs coming from the ends of all of the code 4 runways present. The CAP 168 rules deviate here, giving a larger radius of 4000m to the main runway and 3000m to other code 4 runways.

Figure 3: Comparison of IHS surface for a pair of code 4 runways using Aerodromes 139 and CAP 168 guidance.

We have been for a whistle stop tour through the main differences between OLS rules according to the two sets of guidance which affect different aerodromes in the UK. The departure of the UK from the EU would appear to still be manifesting itself in variety of OLS requirements present among different aerodromes. In the coming years the new OLS surfaces have the opportunity to make everything more uniform, with the caveat that they are also far more malleable to the requirements of individual aerodromes. In the meantime, if you are a developer or airport navigating OLS requirements for a new development, Pager Power has the experience, capability and understanding to model both the existing and proposed OLS for aerodromes in all jurisdictions. Pager Power has assisted developers and aerodromes worldwide with OLS and other complex technical issues, facilitating new development of buildings and renewable energy projects in 61 countries worldwide.

More on the new ICAO OLS surfaces can be found here.

More on Pager Power’s new ICAO OLS modelling can be found here

About Pager Power

Pager Power undertakes technical assessments for developers of renewable energy projects and tall buildings worldwide. For more information about what we do, please get in touch.

References

[1] ICAO State Letter (Reference AN 4/1.1.58-23/33)

[2] CAA, Aerodromes, UK Regulation (EU) 139/2014

[3] CAA, Civil Aviation Publication 168 Licensing of Aerodromes, Edition 12

[4] ICAO, Annex 14 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, Ninth Edition, July 2022 Volume I

[5] CAA, SAFEGUARDED AND OBSTACLE LIMITATION SURFACES – LONDON CITY AIRPORT, 2004

[6] FAA, Federal Aviation Regulations Part 77, Objects Affecting Navigable Airspace

[7] EASA, Certification Specifications and Guidance Material for Aerodrome Design, Issue 6, 2022

Thumbnail image accreditation: Frans Zwart, London City Airport (2010) from Wiki Media Commons. Last accessed on 16th July 2025. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:London_City_Airport_Zwart.jpghttps://www.pagerpower.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/London-City-Airport-thhumbnail.jpeg